Recently, Scott Lindgren posted a kayaking clip of me hurtling down a low volume slide in Norway before flying through the air; this clearly caught the attention of the internet world and has been shared quite prolifically. It’s quite amusing to read the spectrum of comments ranging from “wow”, and “cool”, to “idiot”, or “ego-driven stupidity”. When I look at the slide now, I can safely say that I would not do that again, but at the time it seemed a perfectly reasonable proposition.

Like many “extreme” clips you see on the internet, this snapshot represents a culmination of many years of experience, experimentation, practice, and preparation. At this stage in kayaking history (2002), slides were a big thing. Creek boats were in rapid development, and the boundaries were moving quite fast, as they do in our relatively young sport of whitewater kayaking.

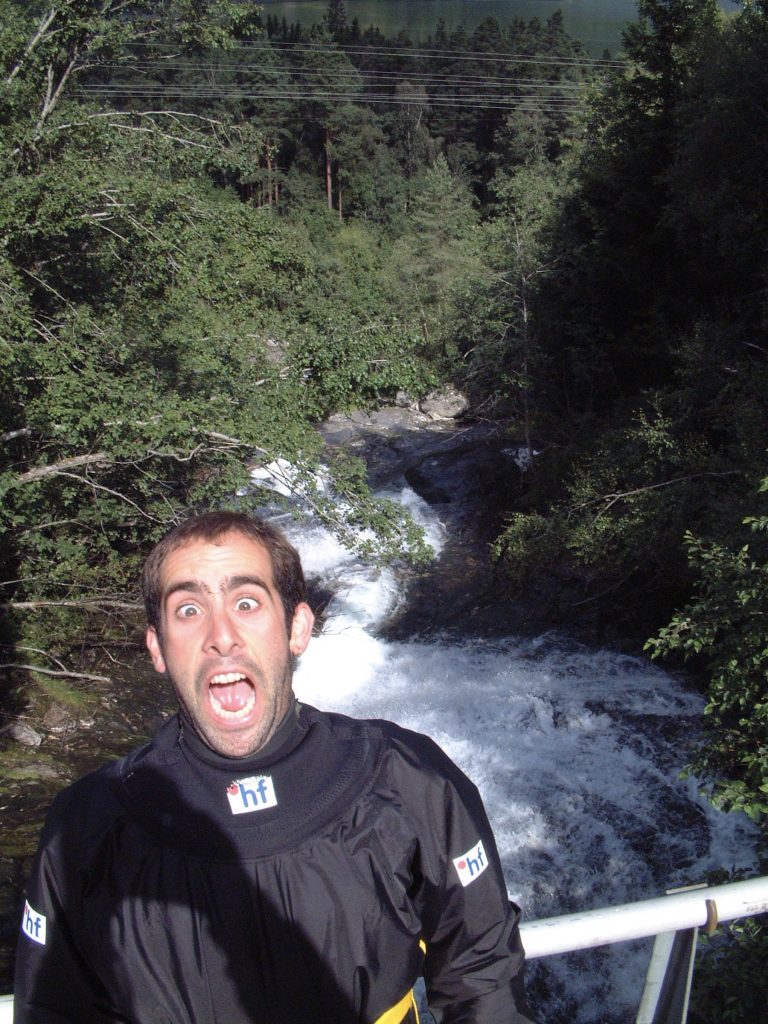

Allan Ellard and I, partners in crime, warriors, were in our third season in Norway, and we were overwhelmed by the range of possibilities in our chosen neighbourhood, Voss. We spent a lot of time driving around looking for new rivers and more significant challenges.

After acclimatising on local favourites like the Branseth and Myrkdal Slides, we found and ran bigger slides like the Tunnel Drop, Lake to Lake, Hommedal Slides, and Buttcrack Creek (better known as Vangjolo to locals in Voss). Then we saw Scott’s latest film where Dustin Knapp and Dave Persolja ran Tenaya Creek; we were blown away, and inspired to find something similar in Norway.

After many kilometres in Western Norway looking at streaks of water running down gigantic slabs, we finally saw something out the car window which could be a possibility; Flatekval Elva in Eksingadalen.

Walking up to the creek, we began to feel nervous when we saw how possible it was. It looked like we could do it. The corner in the middle looked like a problem, with a chance of sliding out of the river bed (similar to Buttcrack; see the video below or ask Anton Immler himself about that one) or maybe catching air and losing control.

We paddled the Pyranha H2 at the time, which was a flat bottomed creek boat, not dissimilar to the Burn III. We had paddled this boat for a few years at this stage and loved it. We also did not agree with the school of thought that edges had no place on creeks. At this stage, many of the competitors’ creek boats were round bottomed sausages. We felt that on this particular slide, specifically the corner, that if we edged our boat away from the corner, the bottom edge would help to trap water and form a kind of a buffer wave under the boat to help it track around the corner.

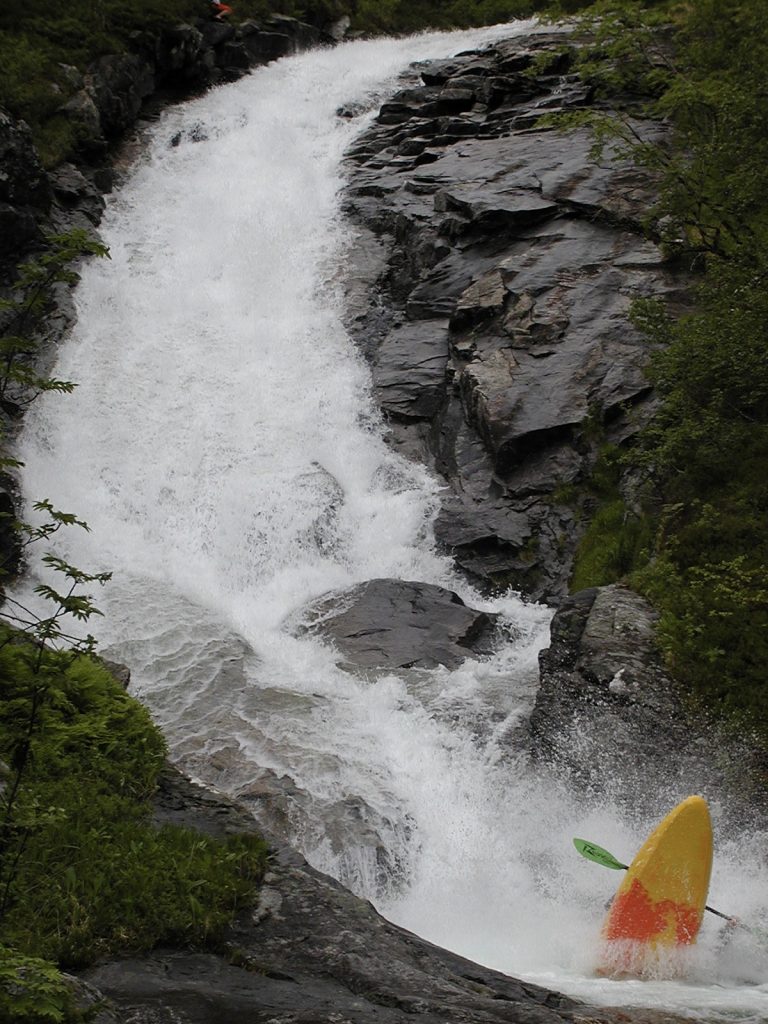

I doubt that anyone who knows Allan and myself well would class us as risk takers; we tend to allow quite large margins for error. We discussed in depth how we would do this, and what kind of safety we’d use. Allan had a pair of heavy duty elbow pads that he made as a project at high school which we shared for the day. If we had a full face, we would have shared that too! We decided we were not 100% sure and made a plan to run the slide from halfway, starting just above the corner so there would be less speed into the corner. This worked beautifully, and we both had clean lines left of the kicker, then we ran it from the top, tracked around the corner, and had clean, smooth lines. We noted that there were slides further up the river, but we were pretty satisfied with the day already and headed home with smiles on our dials.

Olaf Obsommer and Jens Klatt were in town and thought the photo looked pretty spectacular. We told them there was even more upstream, so they decided to come and film. The water level was slightly lower, and we headed further upstream and ran another high-speed combination of slides. We hoped we could link these together with the big slide, but the midsection was a bit too dodgy.

Al and I discussed at length if the lower water level would mean that the boat would travel slower because of extra friction on the rock, or faster with less surface tension from the water and potentially less build-up of a buffer under the edge of the H2 when tilted up on its left side. After the successful run from the day before, we decided to find out. With the extra protection of a motocross top borrowed from Arnt Schaftlein, I went first. I sensed quite early that I struggled to get the boat to track early to the left and flew straight on to the kicker and started flying. I still fantasise to this day about shifting my upper body weight to the right to land boat down, but it just went too fast for me. I landed on my paddle and elbow, I kept both hands on the paddle and sprained my wrists, and in the pool below I felt disappointed in myself for not nailing the line.

Allan wisely decided that the lower water level was not ideal, though I’m sure he would have managed it better than me.

The result of our day was a broadened horizon, a demotion from raft guide to shuttle driver for a week because of some sore wrists, and some pretty cool video footage.

If you’re interested, you can see the full clip in Olaf’s film below:

The clip starts at 20:55, but the film includes some excellent footage of some top paddlers of the time doing some equally impressive stuff and doing a better job of keeping their kayaks on the water.

You may have noticed that this kind of paddling is hard on the kayak, and I can promise you it will severely shorten the life of your boat. Yes, we were sponsored, so thanks to Pyranha for giving us the chance to experiment and contribute to the evolution of Pyranha Kayaks.